April of 1968

Was the April 1968 Car and Driver the best car-magazine issue ever?

By Paul Ingrassia

NAPLES, FL. — The main attraction at Revs Institute, understandably, is the Miles Collier Collection of 115 classic cars: Duesenbergs, Ferraris, Hispano-Suizas — the usual suspects, except that the cars are especially unusual. But the Institute’s automotive library holds underappreciated gems.

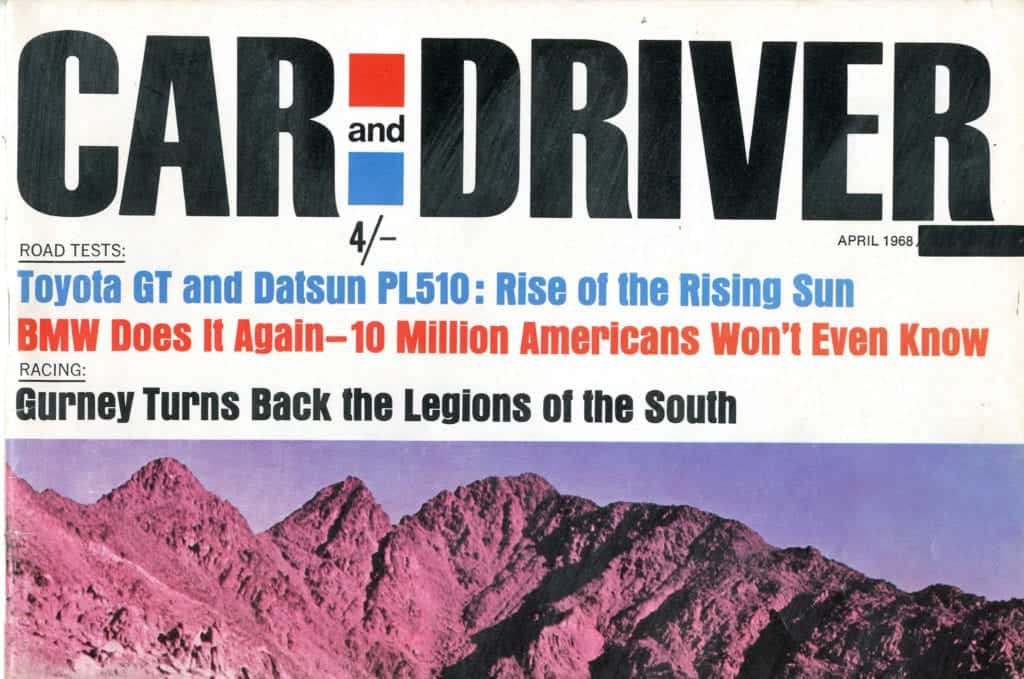

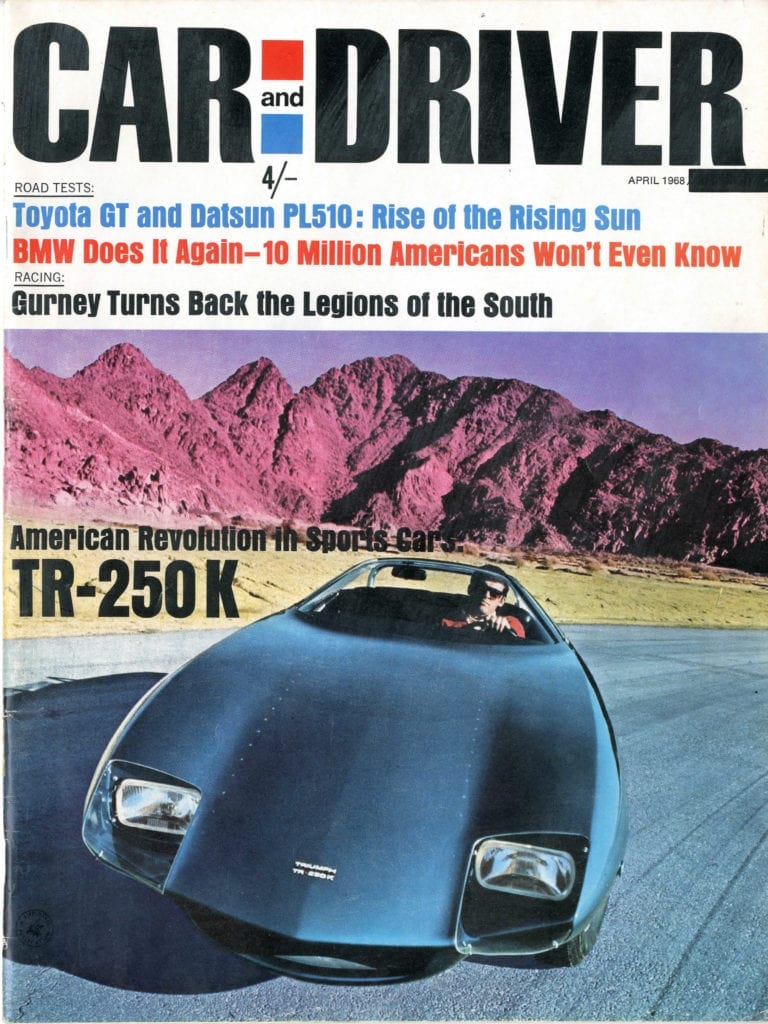

It has 20,000 automotive books and periodicals in four languages: English, French, German and Italian. The first issue of The Car, A British magazine that began publication in 1900 is there. So is every issue of Car and Driver, including one that might be the best single issue of any automotive magazine ever published.

The Car and Driver issue of April, 1968 — exactly 50 years ago — featured signature essays by two all-star, and now deceased, automotive journalists: David E. Davis Jr. and Brock Yates.The essays were not only wonderfully entertaining, but also remarkably prophetic. (That issue, along with dozens of other automotive periodicals past and present, is available for reading in Revs Institute’s library.)

In “Turn Your Hymnals to 2002,” Davis extolled the attributes of the BMW 2002. (https://www.caranddriver.com/reviews/1968-bmw-2002-review) This modestly styled car presaged the BMW 3 Series, laid the groundwork for BMW’s success in America and beyond, and redefined automotive luxury as sophisticated functionality instead of useless ornamentation. And in “The Grosse Pointe Myopians,” Yates described in rich, plaintive detail the introverted tunnel vision that led, eventually, to the bankruptcies of General Motors and Chrysler, and the near-miss for Ford. (https://www.caranddriver.com/features/the-grosse-pointe-myopians-feature)

That issue offered more than those two essays, of course. An article headlined “Toyota GT and Datsun PL510” forecast the rise of Japan’s auto industry, which would manhandle Detroit on its home turf 15 years later. “Gurney Turns Back the Legions of the South” described Dan Gurney’s racing win at Riverside, Calif. over his good ol’ boy rivals.

The 400-hp Oldsmobile Toronado, a Detroit heyday muscle car, got an approving nod. And Davis and Yates had their regular columns — Yates’s a missive against “vehicular law enforcement,” Davis’s a paean to studded snow tires — though neither was as memorable as their signature essays in that issue.

It’s worth pausing here to acknowledge the broader backdrop of 1968. It was perhaps the worst year in modern American history. That April brought the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Just two months later Bobby Kennedy was gunned down. The Democratic Party’s convention that August brought pitched battles between police and protesters on the streets of Chicago. Personal passions — baseball, music, golf, automobiles, etc. — doubtless provided relief for many.

In “Turn Your Hymnals to 2002” (okay, the headline was overtly reverential), Davis declared that automotive performance consisted of more than a monstrous, huge-displacement engine mounted in a car that could hardly take a curve. The alternative: the BMW 2002 sedan with a high-revving multi-valve engine and taut suspension in a lightweight, compact package that could run with many an American rival. Alas, he declared, this concept was beyond the appreciation of America’s automotive-conformity masses.

“In the suburbs,” Davis wrote, “Biff Everykid, Kevin Acne and Marvin Sweatsock will press their fathers to buy HO Firebirds with tachometers mounted out near the horizon somewhere and enough power to light the city of Seattle, totally indifferent to the fact that they could fit more friends into a BMW in greater comfort and stop faster and go around corners better and get about 29 times better gas mileage.”

The four-cylinder, 114 horsepower 2002, he added, produced performance beyond its numbers. It blended fun and functionality, like marrying “a pretty girl who will expertly cook, scrub floors, change diapers, keep the books and still be the greatest thing since the San Francisco Earthquake in bed.” (Yes, that analogy was blatantly sexist. It was a different era then. One hopes.)

By the end of the 20th Century, BMW would be outselling Cadillac in the United States. Davis’s hymn foreshadowed the future.

Yates’s essay was more directly prophetic, even though “The Grosse Pointe Myopians” was a slightly off-target headline. By the 1960s, the preferred homestead for Detroit’s automotive elite was shifting from east-side Grosse Pointe to the northwest suburbs of Birmingham and Bloomfield Hills. No matter. Yates was absolutely on target.

The Detroit auto industry wasn’t growing as fast as forecast in those American boom years, Yates observed, while sales of imported cars were gaining traction. The Big Three (and American Motors) were missing big trends. Americans were getting a plethora of new choices — airline tickets, boats, travel — on which to spend their disposable dollars. And young American hot-rodders wanted better performance as opposed to chrome-laden land yachts. None of that, however, penetrated the inner sanctums of America’s car kingdom.

“The auto industry is an immense upper and upper-middle-class family,” Yates wrote, “with congregating points at half a dozen country clubs, the London Chop House and the Detroit Athletic Club. Here, information and gossip is exchanged about their parochial little world in an incessant babble that reveals a unique narcissism and widespread ignorance of the world outside.”

Forty years later — March 2008 — the collapse of investment bank Bear Stearns started the chain reaction that prompted the bankruptcies and bailouts of GM and Chrysler. Anyone who remembered the Car and Driver issue of April 1968 already knew the story.