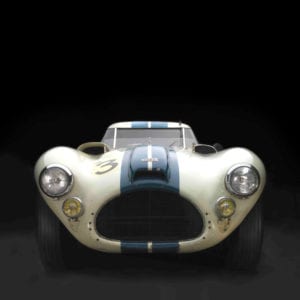

The Cunningham C-4RK Looked—and Raced—like a Cougar in a Bad Mood

The 1952 Le Mans start was the usual jail-break, a rabble of polo shirts and pudding-bowl helmets sprinting across the track, diving into getaway cars, laying down swerving burnouts. They raged over the rise toward the Dunlop bridge.

At the fast end behind the pole-sitting supercharged 4.5-liter Talbot was John Fitch’s Cunningham C-4R roadster and the menacing Cunningham C-4RK coupe, a cougar of a car driven by Phil Walters. The Talbot and Fitch veered through the Esses first, and Walters, the most underrated American racer of the postwar era, raged after them, hot on the scent.

His coupe’s countless scoops and slots and ducts devoured French oxygen. Ranks of gaping louvers along his car’s flanks bristled like hairs standing out on a cat’s back. The Talbot, Fitch, and Walters snaked through Tertre Rouge and out to the limitless wilderness of Mulsanne’s 3.7-mile straight—when Walters pounced.

The C-4RK leapt forward, its four-carb 331cid Chrysler Hemi V8 yowling, the low, crouching bodywork cheating the air … and simply blasted ahead.

In the pits it was four long minutes before the field reappeared … but here came Walters and his angry cougar, the white-with-blue-striped No. 2 leading the first lap of its first race, the most important road race on earth—the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Briggs Cunningham, nonpareil American sportsman, must win Le Mans using American drivers in an all-American race car … and victory was only 24 hours away!

Well, no. Le Mans is a cruel mistress. Continuing even to today, racing 24 hours at Le Mans defies rational calculation. Ask Toyota. Walters maintained a racerly pace, holding the C-4RK in 3rd place for four wearing hours. When it came time for the first driver change, Indianapolis star Duane Carter, a master in Champ cars, climbed into the cougar, raged out—and promptly slid it axle-deep into the sandtrap at Tertre Rouge. He toiled two bitter hours digging the car out … all hope of victory gone.

The Le Mans evening wore on, the Cunninghams’ blistering speed proving both a virtue and a liability. The 5-speed gearbox tried in practice was a failure, so all three raced with rugged 3-speeds. But hauling the heavy 2410 lb. C-4R roadsters and 2450 lb. C-4RK coupe down from speed was proving too much for their 13-inch Alfin drum brakes. Each wheel included forced-air ventilating backing plates, but hellish braking temps were cracking the backing plates, they had no spares, and the cooling was insufficient in any case to relieve severe brake fade. With no choice, the drivers had to rely on downshifting and engine-braking to help slow the cars … but the wide-ratio 3-speed gearbox made over-revving during downshifts all but inevitable. Saturday night, both the Fitch C-4R and Walters’ C-4RK retired with destroyed valvetrains.

This left only the C-4R roadster of owner Briggs Cunningham and Bill Spear running. Heroically, Cunningham drove 19 straight hours before passing the car to Spear. They finished a brilliant 4th overall—Cunningham’s personal best Le Mans during many years of trying.

Even still, the C-4RK, Phil Walters’ angry cougar, left its mark. In peak form early in the 24 Hours, it set the fastest lap of any Cunningham team car. Its closed bodywork proved its worth, as well, registering the highest speed on Mulsanne Straight—150.24mph versus the roadsters’ best of 146.21mph. Perhaps most impressive, its fastest race lap, an average of 105.6mph, was higher than the fastest lap of the 1952 victor, Mercedes-Benz’s 300SL.

The “K” in C-4RK is a nod to pioneering Swiss-born German aerodynamicist Wunibald I.E. Kamm, who worked with Ferdinand Porsche before the war and was brought to the U.S. after the war. The designer of the Cunningham C-4Rs, G. Briggs Weaver, was aware of Kamm’s theories, and after designing the C-4R roadster, he set about designing a low-drag coupe version of the otherwise identical car that would excel on the long, high-speed Mulsanne Straight, Le Mans’ dominant feature.

The C-4RK was given a sloping truncated tail, in keeping with, believed Weaver, Dr. Kamm’s low-drag theory. Briggs Cunningham then invited Dr. Kamm to Palm Beach to inspect the finished car. As noted by Peter Brock in Peter Bodensteiner’s monograph of the C-4RK, Dr. Kamm commented that designing such a car requires spending testing time in the wind tunnel. This fell somewhat short of an endorsement of the C-4RK, and Brock, the master of Kamm-tail design with his definitive Shelby Daytona Coupe, explains why. In Kamm’s practice, the roofline should taper rearward no more than a scant seven degrees, effectively attaching airflow to its surface, thus avoiding turbulence and drag. The tail should then end abruptly, releasing the air pressure rearward. The C-4RK’s tail, however, radiuses steeply downward from its peak, missing this key Kamm principle.

The C-4RK successfully reduced drag nonetheless, giving the coupe far superior top speed to the roadster. It also protected the driver from constant wind buffeting, which roadster driver John Fitch found seriously fatiguing. The tradeoff in the C-4RK was a certain claustrophobia—which didn’t bother the stalwart Walters a bit.

After Le Mans, Walters’ cougar did well in the U.S., winning in 1952 at Giant’s Despair Hillclimb, Allentown and Thompson, and finishing 2nd to Fitch’s roadster at Elkhart Lake. In 1953, after a DNF at McDill AFB in Florida, the C-4RK returned to Le Mans, but 1953’s sleek new C-5R roadster for Fitch and Walters got the team’s attention. Charles Moran and John Gordon Benett drove the C-4RK, though its Le Mans performance was slower than in 1952. Still, the car finished 10th, somewhat overshadowed by the C-5R’s fine 3rd and Cunningham/Spear’s 7th in a C-4R roadster.

The C-4RK raced once more for Cunningham in 1953, Moran gaining a 6th at Turner AFB. Moran then purchased the car and raced it regularly in SCCA’s B-Modified until retiring it in 1957. In 1970, Briggs Cunningham bought it back for his Costa Mesa, California collection. In 1986, Miles Collier bought the entire Cunningham Collection. Today, the C-4RK is part of the Miles Collier Collections, on display at Revs Institute in Naples, FL.